Restore, Work, Destroy: An EC2 lifecycle

Most of the buzz around virtualized IT infrastructure focuses on dynamic scaling – that is, increasing the number of machines when load is high and decreasing when load is low. There is huge value in being able to do this, but there are other valuable opportunities which get less attention. The opportunity that I am most excited about is temporary infrastructures.

Now, temporary infrastructures have received some attention but the focus is generally limited to variations of batch processing. I’d like to talk about another possibility: launching applications only for the time that you need them.

A Just-in-time Issue Tracker

Launching an application, using it, and shutting it down is interesting but it’s hardly mind blowing. I’m going to kick it up a notch by demonstrating how to routinely persist an application and its data between machine instances using Amazon EC2, EBS volumes, and Rudy.

Imagine being able to run an issue tracker for your team, only during business hours. Off hours the machine is shut down (along with the applications running on it). Instead of paying $75 / month for the smallest EC2 instance, you’re now paying around $18. And there’s a bonus: you’ll be creating full daily backups as part of your regular process.

I’m using JIRA for this example because it is a popular bug and issue tracker that’s familiar to many people.

What you need

- An Amazon Web Services (AWS) account and credentials

- Some experience running tools on the command-line

- Rudy installed on your machine

- A JIRA License (optional)

- 5 minutes

Note: I am running this demonstration from OS X, but Rudy runs on Windows and Linux as well.

Initial Installation

After installing Rudy, download the configuration file for this demonstration. Before running the first command it’s important that you understand what it does:

- Launch an instance of Linux in EC2

- Create a user to run the JIRA application

- Open port 8080 (for your IP address only)

- Create a 10GB EBS volume

- Download, install, and start JIRA

The meat of the configuration looks like this:

install do

before :startup

adduser :jira # Create a user on the linux

authorize :jira # machine to run the app.

network do # Open access to port 8080

authorize 8080 # for your local machine.

end

disks do # Create an EBS volume where

create "/jira" # JIRA will be installed.

end

remote :root do

disable_safe_mode # Allow file globs and tildas.

raise "JIRA is already installed" if file_exists? '/jira/app'

jira_archive = "atlassian-jira-standard-3.13.5-standalone.tar.gz"

uri = "http://www.atlassian.com/software/jira/downloads/binary"

wget "#{uri}/#{jira_archive}" unless file_exists? jira_archive

cp jira_archive, '/jira/jira.tar.gz'

cd '/jira'

mkdir :p, '/jira/indexes', '/jira/attachments', '/jira/backups'

tar :x, :f, 'jira.tar.gz'

mv 'atlassian-jira-*', 'app'

chown :R, 'jira', '/jira'

ls :l

end

after :start_jira

endWhen you’re ready, run the following command:

$ rudy --config path/2/jira.rb install

Once this command finishes, you’ll be able to grab the the public DNS for your new EC2 instance by running:

$ rudy --config path/2/jira.rb machines

JIRA Setup (optional)

This step requires a JIRA license. You can generate a trial license or skip to the next section.

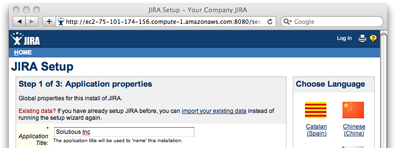

Open JIRA in your browser by copying and pasting the public DNS info into the address bar. Make sure to specify port 8080! It should looking something like:

http://ec2-75-101-174-156.compute-1.amazonaws.com:8080/

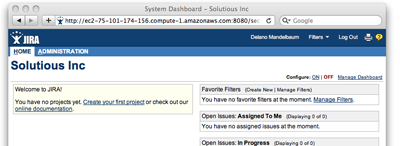

Continue through the setup wizard and you should end up with a page that looks like this:

You can use JIRA as much as you like. Create a project, file a bug, etc… In the next section we will destroy this instance and later, through the magic of television, restore it back to the state you left it.

Destroy!

This is the exciting part where we destroy the instance and the disk! This next command will:

- Stop the JIRA application

- Create a snapshot of the disk (EBS volume)

- Destroy the disk (forever)

- Shutdown the instance (also forever)

The relevant configuration looks like this (note how the destroy routine refers to dependencies for the first two steps):

destroy do

before :stop_jira, :archive

disks do

destroy "/jira"

end

after :shutdown

end

archive do

disks do

archive "/jira"

end

endTake a deep breath and run:

$ rudy --config ruby/unix/jira.rb destroy

The instance is now gone. You can try to reload JIRA in your browser but sadly and perhaps slightly frightening, it’s gone.

Restore

And finally the moment we all been waiting for: restoring JIRA to its previous glory. This command will:

- Create a new EC2 instance

- Restore the disk from the most recent backup

- Start the JIRA application

Here is the relevant configuration:

restore do

before :startup

adduser :jira

authorize :jira

network do # Open access to port 8080

authorize 8080 # for your local machine

end

disks do # Create a volume from the

restore "/jira" # most recent snapshot

end

after :start_jira

endRun the following command:

$ rudy --config ruby/unix/jira.rb restore

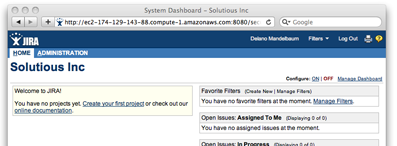

Note that even if you skipped setting up JIRA, it’s in the same state as you left it without having to reinstall in. If you did setup JIRA, you’ll notice that it’s in the same state as you left it too. However, notice how the public DNS is different. That’s because it’s an entirely new machine with an entirely new disk.

Don’t forget to destroy the instance again when you’re done!

Final Thoughts

This was a very simple demonstration. What is most interesting to me is that backups are implicitly included in this lifecycle. Not only does it cut the cost of running a machine by over two thirds (assuming business hours), it provides complete daily backups as part of the regular process.

And of course, if you were to use this configuration, there are other things you’d probably want to do (install MySQL, modify the JIRA configuration, etc…) but it already gives you a look into what is possible with temporary infrastructures.

What do you think: would this kind of workflow be useful for you?